In the summer of 1946, while vacationing in nearby Golfe-Juan with his partner Françoise Gilot, Pablo Picasso made a chance visit to the annual pottery exhibition in Vallauris, a small town on the French Riviera known for its centuries-old ceramic tradition. What began as a casual outing quickly transformed into a pivotal moment in the artist's life, one that would lead him to settle there and revolutionize the world of ceramics.

A Serendipitous Encounter with Ceramics

Vallauris, nestled between Antibes and Cannes, had long been a hub for pottery, with workshops producing everything from utilitarian cookware to artistic pieces. Post-World War II, the town's industry was struggling, but its annual exhibitions showcased local talent. At the 1946 show, Picasso met Suzanne and Georges Ramié, owners of the Madoura workshop. Intrigued by the possibilities of clay, he accepted their invitation to experiment with their kilns.

Within days, Picasso created a handful of decorated plates and small sculptures. The tactile, three-dimensional nature of ceramics captivated him, a medium that blended painting, sculpture, and craft in ways his previous work had only hinted at. He returned in 1947 to collect fired pieces from the year before, and by 1948, enthralled by this new frontier, he moved to Vallauris with Gilot and their young children, Claude and Paloma.

A New Chapter in the Post-War Mediterranean

After the horrors of World War II and his time in occupied Paris, Picasso sought the light and serenity of the Mediterranean coast—echoing his Spanish roots. He had already spent time in Antibes in 1946, producing joyful, mythological works. Vallauris offered more: a quiet, unpretentious town where he could escape fame while immersing himself in a community of artisans.

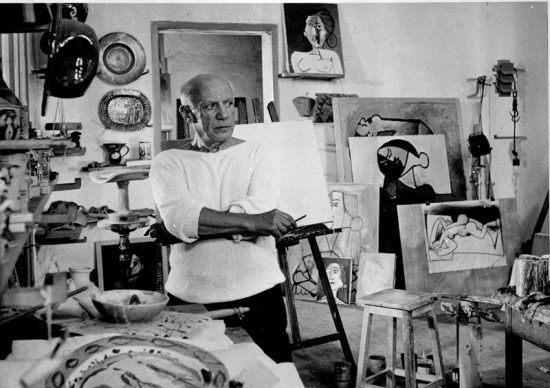

Settling into a modest villa called "La Galloise", Picasso collaborated closely with the Madoura workshop. Over the next two decades (though he lived there primarily from 1948 to 1955), he produced over 4,000 ceramic pieces—playful vases, plates, pitchers, and sculptures featuring owls, bulls, fauns, and Mediterranean motifs.

.jpg)

These works were revolutionary: Picasso treated clay like canvas, blending ancient forms with modern whimsy. Editions made them accessible, democratizing his art in an era of post-war austerity.

Revival of a Town and a Personal Renaissance

Picasso's arrival revitalized Vallauris. Struggling potters gained international attention, attracting artists like Marc Chagall and Jean Marais. The town became a mid-20th-century creative hub. In gratitude, Picasso donated works, including the bronze Man with a Sheep for the town square and his monumental mural War and Peace (1952–1959) in a deconsecrated chapel—now the National Picasso Museum.

This period was one of personal happiness for Picasso—family life, political engagement (as a Communist Party member advocating peace), and boundless creativity. Even after moving to Cannes and Mougins, he continued ceramics at Madoura until his death in 1973. He even secretly married Jacqueline Roque in Vallauris in 1961.

Ultimately, Vallauris drew Picasso with the promise of reinvention: a humble craft elevated to high art, in a sunlit town that mirrored his joyful, post-war spirit. It wasn't just a residenc. It was a transformative haven where clay became his playground.